-

Population384,000 in 2020

-

EDA Investment$820,000 in 2017

In the 1950s, the Claiborne Corridor bustled with Black-owned businesses and was one of the most successful commercial corridors in New Orleans.

Then came what residents called “the Monster.”

Construction of the elevated Interstate 10 freeway, part of the federal government’s 1960s highway program, tore straight through the community. The highway forced hundreds of businesses to shutter, demolished houses and a massive swath of oak trees, and denied the Black families who remained in the neighborhood equal access to jobs, health care, and other opportunities to build intergenerational wealth.

Today, the life expectancy of residents along the freeway is 25 years shorter than residents in other New Orleans neighborhoods.

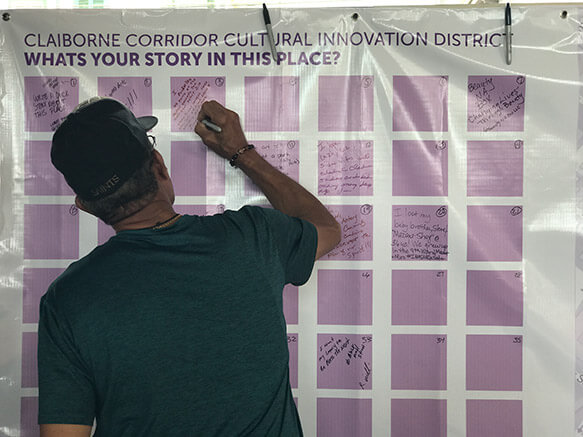

Asali DeVan Ecclesiastes, CEO of Ashé Cultural Arts Center, and Nyree Ramsey, executive director of Ujamaa Economic Development Corporation, are driving a community-led effort to transform the highway underpass into a gathering spot for the neighborhood—a place to host local businesses, musical performances, and community events. They also want to make the area safer for residents and more resilient to persistent flooding, and they aim to create jobs and opportunities that reduce the area’s gaping health disparities.

In a place where the interstate once destroyed opportunities for residents, the federal government is now listening to what the community needs to heal and thrive. In 2017, EDA invested $820,000 in the Claiborne Corridor’s Cultural Innovation District to support the design and construction of a public market under the bridge, with groundbreaking expected in 2022.

The EDA’s investment not only helped draw other investors to the project, but it also held space for equity in the effort, which took years of planning, neighborhood meetings, and resident input to ensure redevelopment of the 19-block area was community driven. Without that guaranteed federal funding, an outside developer could have bought up the land and ignored the desires of residents—a gentrification story all too common in the city.

“This anchor investment is catalytic. The ability to hold space is just as important for economic development as creating jobs,”

–Asali DeVan Ecclesiastes

“The EDA grant helped us reserve that space for residents to be able to take that time we needed and to make sure we reserve opportunity for us. This is the type of project that can be transformative for a community that has long been used to disinvestment,” Ecclesiastes said.

Credits

Images (in order of appearance):

- The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.325.5134

- The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.325.5137

- The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.325.5136

- The William Russell Jazz Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, MSS 520.1397

- The William Russell Jazz Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, MSS 520.1396

- Image courtesy of Angela Calonder

- Image courtesy of Greg Miles

- Image courtesy of Colloqate Design

- Image courtesy of Nyree Ramsey, Ujamaa CID and Colloqate Design

- Image courtesy of Nyree Ramsey, Ujamaa CID and Colloqate Design

- Image courtesy of Nyree Ramsey, Ujamaa CID and Colloqate Design

- Image courtesy of Colloqate Design

Explore More

-

Park City, UtahTransforming a mountain “ghost town” into a tourist destination

-

Bloomsburg, PennsylvaniaRetaining hundreds of jobs through disaster relief in Columbia County

-

East Los Angeles, CaliforniaReplacing a reminder of economic distress with "a symbol of growth and reinvestment"